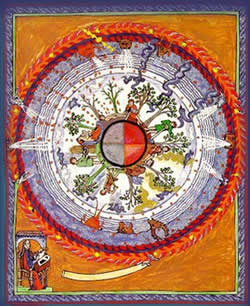

Wheel of life

Hildegard

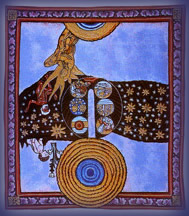

had her texts ‘illuminated’, i.e. illustrated. This practice

was not merely decorative, as illuminations were thought to be at times

more potent than the words themselves. In some (e.g. the illustration

above) Hildegard

can be seen as a tiny seated figure

with slate ready to hand as she sits enrapt in some prodigious revelation.

The

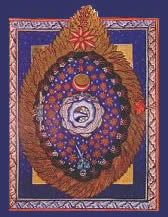

cosmic egg

I,

the fiery life of divine essence, am aflame in the beauty of the meadows.

I gleam in the waters, I burn in the sun, moon and stars...

(Hildegard’s perception of the

divine as lux vivens)

Hildegard herself was burning with inspiration, and this comes out in her music and the illuminations [7] of her works. Her writings often speak of viriditas, which can be translated as ‘greening’, and this is how the universe appeared to her, brimming with creativity and life. She also uses this term in discussing theological concepts. For instance, she describes Mary, the mother of Jesus, as the viridissima virga: by giving life to humans through the life she gave to Christ, she, too, contributes to the ‘greening’ of the world.

Her visions varied in content, but she repeatedly interpreted them in a way intended to carry forward an agenda of ecclesiastical and secular reform. They are also significant as they have a strongly feminine nature and yet were accepted by the patriarchal establishment.

Like all women of her time Hildegard was born into a cultural inheritance that diminished the standing of women. The early church fathers had promulgated the view that, because of ‘Eve’s disobedience’, women were to be forever subordinate to men. The medieval church also embraced the silencing of women allegedly prescribed by the apostle Paul. [8] The only way women such as Hildegard could find an audience was for them to speak with vox Dei, the ‘voice of God’. And when her visions were given the papal seal of approval she was granted—up to a point—this right to be heard.

Hildegard herself preached against heresy, and on the whole she stayed within acceptable boundaries as regards basic church doctrine. At the same time she managed to slip in some innovative ideas. For example, while on the one hand appearing to agree that women should not be priests, she nonetheless goes on to suggest that nuns attain the authority of the priesthood through their marriage to Christ: “...in her Bridegroom she has the priesthood and all the ministry of [the] altar, and with Him possesses all its riches...” Surely here she is finding a way to claim an authority normally only assumed by men.

“I composed and chanted plainsong in praise of God and the saints even though I had never studied either musical notation or singing...”

Six days of creation

In contrast to the rather mild music of her time, the works Hildegard created were rhapsodic, indicative of the ecstatic flights she must have been experiencing in her inner life.

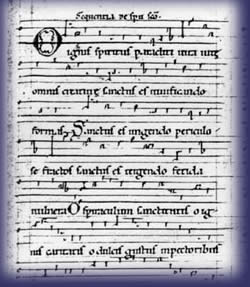

O

ignis spiritus

detail

of manuscript

“O

fire of the Holy Spirit

life of the life of every creature,

holy are you in giving life to forms...

From you clouds flow, air flies,

rocks have their qualities,

rivers spring forth from the waters

and earth wears her green splendour”

From the moment she entered the life of the monastery, Hildegard was exposed to the singing of the ‘divine office’, [9] which, according to Benedictine rule, occurred eight times a day. When she herself became a nun she would have been involved in chanting for almost four hours a day, and although she had no formal training, this exposure prepared the foundation for her musical creativity. In addition, when she did come to compose, she would have at hand both the monastery scriptorium—where copyists could transcribe her work—and a skilled and practiced body of performers.

Hildegard described music as a means of recreating the rhythm of the universe. In contrast to most liturgical music of the day, her chants have a very wide range, soaring up and down across several octaves. She wrote profusely, composing [10] 77 chants and a musical drama, Ordo Virtutum, “Play of virtues”. She was able to combine elements of her theology, philosophy, cosmology—and even medicine—into what she called symphonia, a concept that to her meant not only the harmony achieved through the skilled juxtaposition of voice and instrument, but also spiritual unity, the healing of discord between heaven and earth.

When Hildegard was 38 her mentor died, and she was elected head of the group that Jutta had attracted to the anchorage. Around 1150 CE she broke from the monastery and established her own convent at Rupertsberg near Bingen. This decision was met with contention from the monks of Disibodenberg, not least because they depended on the land that the nuns often brought with them. Hildegard fought for the independence of her community by seeking the protection of both the Archbishop of Mainz and the Emperor, Frederick Barbarosa. Under her leadership the community became economically successful, and in 1165 CE she established a sister community in Eibingen.

At the age of 60 she went on a preaching tour, an enterprise unheard of for a woman of her time. In the last year of her life, when the penalty of interdict [11] was imposed on her convent for what was perceived as disobedient behaviour, she protested to the prelates: “This time is a womanish time, because the dispensation of God’s justice is weak. But the strength of God’s justice is exerting itself, a female warrior battling against injustice, so that it might fall defeated.” The narrow-mindedness of the prelates had clearly enraged her; in the same breath putting forth the orthodox view of women as weak, she goes on to conjure divine justice as a strong female warrior, perhaps a figure with which she herself could identify.

In spite of her protest the prelates stood firm, and it was only when she wrote a second letter—decidedly more conciliatory in tone—to the Archbishop of Mainz that the interdict was lifted. Six months later she died, age 81. Although she has never been formally canonized, the anniversary of her death—17 September—to this day appears on the calendar of saints.