justice, mercy and the pearl of self-forgiveness

Simulation of the big bang,

NASA library image

What

is primordial chaos but the ether containing within itself

all forms

and all beings, all the seeds of universal creation?

Helena Blavatsky* (1831-1891)

Human beings have often pictured the earliest state of the universe as chaotic, either blindly moving towards the establishment of order or—as in many traditional religions—having form imposed on it by a higher power. Although necessary and occasionally even exhilarating, times of extreme change are considered to be ‘disruptive’ as compared to ‘natural’, and in some cosmologies order and chaos are viewed as polar opposites representing—respectively—good and evil.

It is highly unlikely that most scientists would apply the term ‘evil’ to the chaotic aspects of their own particular field. But a belief in an intrinsic order has nonetheless played an important role in the evolution of science. Physical laws are seen as a manifestation of this order, and the conviction that such laws exist for all systems, no matter how complex, has, for many scientists, been an abiding article of faith.

*Founder of the Theosophical Society and a champion of the unity of humankind.

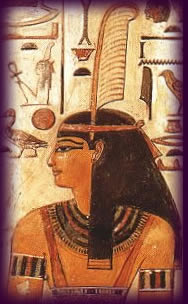

Ma’at with her feather

Ma’at

is worn like an amulet at your throat...

the divine entities reward you with Ma’at,

for they know her wisdom...

XIXth dynasty Egyptian

papyrus

Most existing judicial systems—both secular and religious—have arisen from the desire to maintain order and redress wrongs. Yet for all our wishing it were true, justice is not an absolute, and paradox remains one of the most perplexing facts of human experience: the co-existence of such seeming contradictions as chaos and order, war and peace, life and death, suffering and joy.

The ancient Egyptians—like many of us today—wanted to believe that the universe was an ordered and rational place where things happened for a reason. The word they used for this balanced unfolding of events was the same as their word for ‘truth’, i.e. ma’at. The primary duty of the Egyptian ruler—the pharaoh—was to mirror this universal truth by maintaining law and administering justice. Over time this principle of cosmic order and rightness became personified as a goddess (see left). Pharoahs were often depicted offering up a miniature statue of Ma’at, and in later times judges would also be adorned with her image.

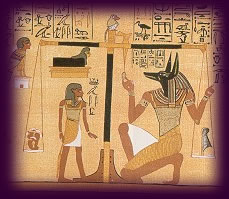

In

the hall of two truths

Papyrus of Ani, c 1450 BCE

The deceased, Ani, watches as the jackal-headed god Anubis supervises the weighing of his heart against the feather of Ma’at.

No

one reaches the salutory west

unless their heart is righteous by doing

ma'at...

There is a kind of epiphany—a spontaneous review of one’s life with a strong sense of meaning and feelings of joy or remorse—that can happen at any time, in any place. Such a summary review has also been a feature of many reported near death experiences—which is undoubtedly the reason that scenarios of judgement have surfaced in so many religions.

In ancient Egypt it was considered worthy to live an authentic life radiant with ma’at. From the papryus scrolls discovered in burials and from images found painted on coffins and inscribed in tombs it appears that then, as now, there were several different views of what might occur after death. But in one common scenario the deceased was led into the “hall of two truths” during passage through the underworld. Here the individual’s truth—symbolised by their heart—was weighed against cosmic truth, represented on the scales by the feather of Ma’at.

It

was believed that if the heart was heavy with wrongdoing, it would outweigh

the feather and the soul would be tossed aside, to be devoured by a monster.

But if the scales were balanced, indicating that the deceased had been

a just and honourable person, they would be able to pass on to the blessed

land in the west.