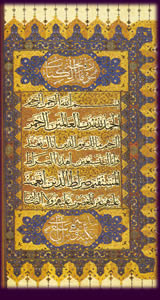

Islamic

calligraphy,

Bismillah, “In the name of Allah”

‘Allah’ was a divine name known in Mecca before the revelation of the Qu’ran; sura 17.110 says “...Call upon Allah or call upon al-Rahman: whichever you call upon, to him belong the most beautiful names.”

Sura 9, ‘Repentance’, is the only chapter that does not begin with the invocation Bismallah al-Rahman al-Rahim. Some tradtional commentators regard this sura as a continuation of the previous one. Whatever the explanation, what is abundantly clear to any reader of the Qu’ran is that Muhammad perceived the revelations as the gift of a compassionate and merciful deity, one who wished to bestow on humankind the best of his wisdom.

Bismillah

al-Rahman al-Rahim

(In the name of Allah, the compassionate, the merciful)

Qu’ran 1:1

A study of religions reveals some fascinating anatomy, layer upon layer of insight and historical revision built around a core of individual experience. The prophet Muhammad, like all religious figures, was a person of his time, and scholars have noted that the earliest* chapters (suras) of the Qu’ran are short, rhythmic sequences that are in the style of pre-Islamic Arab soothsayers.

When he had his first encounter with the angel Jibreel (Gabriel), he was told: “Recite in the name of your Lord (rabb)”, and this is the way the early revelations in the Qu’ran speak of the divine. Some time later, Muhammad began to refer to his god as al-Rahman, ‘the compassionate’, which might lead one to think that—following his initial fear and anxiety as regards having the ability to perform such a task—the prophet felt forgiven of his inadequacies and was now experiencing revelation as a grace.

The word Islam means ‘submission’, the goal of Muslims being to surrender to the will of Allah. Celebrated on the fifteenth night of the Islamic month of Sha’baan, the festival of Lailat-ul-Bara’h reminds Muslims of this, for it is said that on this night Allah records—for the coming year—all the actions it is willed they will perform.

*In

terms of date they were brought forth, not sequence in the final book

(see note at the bottom of the page).

Illustrated

Qu’ran

(16th century, Iran)

The

gift of the Word in the form of the Qu’ran

brought literacy to the people of Arabia, sowing seeds that blossomed

into arts, sciences and other branches of learning.

All

praise is due to Allah, the Lord of the worlds,

the

beneficent, the merciful,

master of the day of judgment.

Thee do we serve and Thee do we beseech for help.

Keep us on the right path...

Qur’an 1:2-6

The first chapter of the Qu’ran is known as al-Fatiha, ‘the opening’. It has been said that this sura represents a request for divine guidance—the seeking of an oracle, perhaps—and that the rest of the Qu’ran is a response to this request.

Muhammed was influenced by and acknowledged the other ‘people of the book’ of his time, the Jews and the Christians, many of whom also believed in a final day of judgement. Rosh Hashanah and the days of awe leading up to Yom Kippur is a time when divine judgement can be affected by sincere repentance, and it seems clear that the festival of Lailat-ul-Bara’h has its antecedents in these observances. For it is said in an Islamic tradition (hadith) that on this night Allah’s mercy descends “to the nearest heavens”. A suggestion that this is a time when it is most accessible to Muslims, a moment, perhaps, when unalterable fate can be changed.

Variously translated as ‘night of forgiveness’, ‘night of emancipation’, ‘night of record’ and ‘night of freedom from fire’, Lailat-ul-Bara’h is spent by some visiting cemeteries, reciting the al-Fatiha and seeking Allah’s compassion for the souls of departed ancestors; for others it is a time to concentrate on their own need for mercy and forgiveness.

Epiphany

(17th century mosque, Isfahan, Iran)

Calligraphy is considered the most sacred of Islamic art forms, in that it recalls the divine Word (i.e. the Qu’ran) through which Allah revealed himself. In the photograph above, Nader Ardalan has captured a mysterious pattern of light on the tilework of the mosque; against the calligraphy on the tiles it might suggest, perhaps, the living presence of the Word.

I

pled for mercy and had a vivid realization of forgiveness

and renewal of my nature. When rising from my knees I exclaimed,

‘Old things have passed away, all things have become new.’

It was like entering another world, a new state of existence...

[An ordinary woman’s account of an experience of forgiveness*]

Christians will know the word epiphany** from the festival of the same name, which celebrates the revelation of the baby Jesus to the Magi. Nowadays it is also used to refer to moments of experience that transcend the ordinary, such as that quoted above, or as pictured in the photograph at left.

It seems patently obvious that much of human suffering is not deserved. At the same time, it is also human nature to ask “why is this happening?” The yearning for order—for a logic to our existence—is strong, but experience repeatedly shows that searching for answers again leads to paradox: i.e. there are times when life is meaningful and there are times when it is not.

There also does not appear to be a ‘logic’ as regards who is granted the kind of forgiveness described in the account above. There are many examples of grace given beyond the apparent deserving of it: in Shakespeare’s play “The Merchant of Venice”, it is said of the quality of mercy that “...it blesseth him that gives and [also] him that takes.” Societies could not function without their rules and regulations, but there are realms of existence that belong only to the soul. And when it comes to the weighing of a life, who can truly say they’ve seen fully into another person’s heart?

*Quoted

in The varieties of religious experience by William James, 1929.

**From Greek epiphainein, ‘to show forth, manifest’,

referring to the appearance of a deity or other supernatural being.