On

the banks of the Jamuna

I heard the flute

and lost my heart to him

who played it so enchantingly

Mira Bai

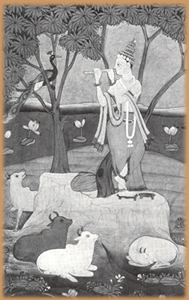

Enchanting the animals

(Miniature, Hyderabad, c 1770 CE)

In the Bhagavata Purana it tells how Krishna soothed the animals with his playing: “cows raise their ears...and the calves stand still... The birds in the forest [are also] there to see Krishna... [They rise into] the trees...[to] hear the sweet vibrations of the flute...”

This paints a wonderful picture for those of us who believe that humans are not the only animals capable of experiencing mystery. At the same time, Krishna’s flute calls to our deepest instincts (symbolised by the animals) reminding us that, even in the midst of our day-to-day concerns, we, too, are spiritual beings.

In a figure like the god Krishna there is a whole host of complexities. There seems to be little doubt that he originated as a pre-Aryan* hero, but so numerous are his forms—mischievous child, supreme Lord, erotic playmate and embodiment of ecstatic love—that it is impossible to distinguish historical fact from the added textures of legend and fable.

It

is also likely that all of these forms are part of a reaction to

the long domination of the priestly caste imposed on the indigenous

people by the conquering Aryans. In

contrast to Vedic and Brahmanical religion, the

worshippers of Krishna seek not for ultimate knowledge and the

perfect performance of ceremony, but

rather spiritual

freedom

and

individual

personal devotion—in which people of all castes and walks of

life, women as well as men, can equally participate.

*Aryan, ‘noble’.

Refers to the tribes of Central Asia who invaded

and conquered the Indian subcontinent, bringing with them much of

what we know today as Vedic literature and theology.

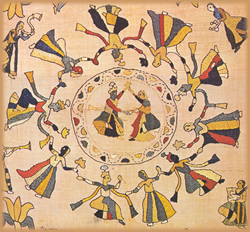

Rasa lila

Over the years, one woman in particular emerged into the forefront: the gopi Radha. In the first picture above, Krishna is alone in the centre of the circle, but in later images, as illustrated in this 18th century embroidery, Radha is with him.

Thus

the gopis went on singing...crying endearingly out

aloud, hankering...for the audience of Krishna. The son

of Vasudeva...

the bewilderer of the mind, appeared directly before

them smiling with His lotuslike face...

To see Him...opened the girls full of

affection...

Bhagavata Purana 32: 1

And so we come to the rasa lila, the ‘dance’, rasa, of lila, ‘divine play’. Lila is a term that dates back to the Vedas, where it refers to the joyous play of the divine manifesting the universe. It is a term often applied to the actions of Krishna, for instance, as in the quote above, where the playing of his flute causes the women of Vrindavana—the famed gopis*—to fall hopelessly in love with him.

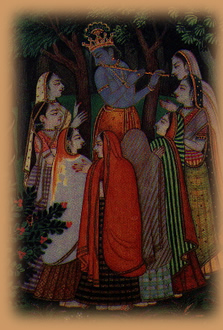

Here bhakti**, the way of salvation through devotion to a personal god, finds one of its greatest blossomings. Already in the Gita, bhakti was presented as an alternative to the path of knowledge (jnana) and the self-discipline practiced by the yogins. But the Krishna presented in the Gita is so majestic and awesome that he is hardly approachable by ordinary human beings.

In the five chapters of the Bhagavata Purana commonly known as the rasa lila, the autumn moon turns full, and Krishna’s love for the gopis erupts. With the sound of his magical flute he calls them to meet with him in the forest, and, surrounded by hundreds of women, he initiaties them all simultaneously into the mystery of divine love: the miracle of the rasa lisa is that each woman believes she alone is the target of his attention. But it goes beyond that, for he teaches them that their own carefree play is an expression of their divinity.

The love between Krishna and the gopi Radha is the subject of the Gitagovinda, the “love song of the dark lord”, composed by Jayadeva in the twelfth century. The verses of this poem, set firmly in the realm of human love and longing, leave no doubt that, for all its sensuousness, the love between these two is divine and eternal, an unending cosmic event. It has been said that, had it not been for the rasa lila, the rich religious tradition of Hinduism might have been overcome entirely during the Muslim domination of India. Although the Muslims cared little for the beliefs of the native population, apparently they could not ignore the love story of Radha and Krishna; the Mughals (1526-1858) in particular commissioned their artisans to depict it.

*Gopi is the feminine form of gopa, ‘cowherd’.

**Bhakti

is a deep personal devotion to a god, a form of worship which arose

in the early centuries CE as a response to Buddhism and in reaction

against Brahmanic ritual. Bhakti can be directed towards any deity,

and has been a distinctive feature of the worship of Krishna since

medieval times.