|

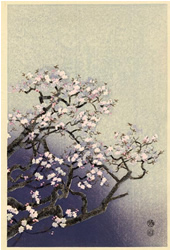

Cherry

blossoms |

The origin of Higan—a seven-day festival marking the vernal equinox, Shunbun-no-hi—is unknown, but it was widely observed in Japan in the eighth century. In 806 CE, the Emperor issued an ordinance concerning its observance, and during the Meiji Era (1868-1912 CE) the government made the day of the equinox a national holiday.

The word higan means “the other shore,” a Buddhist term that comes from the idea that there is a river marking the division of this life from the world of salvation. This river is full of illusion, passion, and sorrow, and only by crossing to the other shore can one gain enlightenment and enter nirvana. It is said that, when night and day are equal (as occurs on the equinox) the Buddha appears on earth to save stray souls and help them make the crossing. Thus the visit to the family cemetery on this occasion is a happy event.

The ritual of offering food and sake to the ancestors developed into another custom typical of the Higan observance, that of giving specially prepared food—most commonly Ohagi, a ball of soft rice covered with sweetened bean paste—to friends and neighbours.

In Japan it is said that the chill of winter finally disappears after Shunbun-no-hi, a time that cherry blossoms—the most popular symbol of spring—first start to appear.