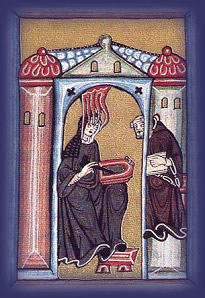

Hildegard with her lifelong friend and scribe, the monk Volmar

“I saw under [the influence of] heavenly mysteries while my body was fully awake and while I was in my right mind. I saw it with the inner eye of my spirit and grasped it with my inner ear...”

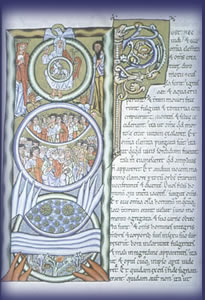

In

the illustration above, Hildegard

depicts

inspiration as tongues of fire, suggesting a powerful

and vibrant experience.

And once again I heard a voice from heaven

instructing me.

And it said, “Write

down what I tell you!”

Hildegard

of Bingen

(1098-1179 CE)

The medieval visionary Hildegard of Bingen was the 10th child born to a noble family in Germany. It was the custom at that time to dedicate [1] such a child to the church, and at the age of 8, she was handed over to an anchoress [2] named Jutta to receive religious instruction. The education available to girls like Hildegard was rudimentary—she was taught to read the Psalter [3] in Latin—and she would later struggle with feelings of inadequacy concerning her proficiency with the language. Yet she was not without opportunity: the attachment of the anchorage to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg meant that she would be exposed to the scholarship typical of such a place.

For

this reason, although it must have been painful, her separation from her

family at an early age was quite possibly fortuitous. At a time when very

few women had a say, life in the Benedictine community allowed her to

develop her diverse and extraordinary talents. In addition to producing

several major works on theology—as well as treatises on natural

history and the medicinal uses of plants—Hildegard would come to

correspond with bishops, popes and kings and speak out openly against

corruption in the church. She was familiar with the science of her day

and often drew on her understanding of the natural world to illustrate

a theological argument. And she left behind a large corpus of music; in

fact, in spite of the dearth of female composers even today, she is probably

the earliest composer of either sex whose biography is known.

Illustrated page from Scivias

Hildegard often saw a brilliant light, inside of which she at times perceived an even brighter illumination she called lux vivens, ‘the living light’. A vision of this living light was capable of dispelling all her sadness and anxiety, and she strove to reflect it both in words and in music.

And it came to pass...when I was 42 years...old, that the heavens were opened and a blinding light...flowed through my...brain. And...it kindled my whole heart and breast like a flame...and suddenly I understood the meaning of...the books.

Hildegard had experienced visions since the age of three, which for the most part she kept hidden from everyone but her teacher and a monk named Volmar—until, that is, she received official approval. It has been said—partly because of her own references to suffering and pain—that much of what she described as ‘visions’ were in fact the side effects of migraines. While it is quite likely she did suffer from migraine, to attribute her creativity entirely to pathology would be inappropriate. Perhaps it would be more useful to say that she drew on such visual and auditory side effects to inspire her creative spirituality—turning what was essentially a curse into a blessing and a gift.

In 1141 CE she had a vision that would change the course of her life (see quote above). However “although I heard and saw these things, because of doubt and low opinion of myself and because of diverse sayings of men, I refused for a long time [the call].” She was living during a period when there was much religious foment, and—although always believing herself that her visions were authentic—she wanted them sanctioned by the church.

She wrote to the abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, himself a noted mystic [4], who brought her to the attention of Pope Eugenius. Luckily for Hildegard, Eugenius was an enlightened individual who encouraged her work. With the publication of her first book Scivias [5], her fame began to spread. People flocked from all parts of Germany to seek her counsel, and she eventually became known as the Sibyl [6]of the Rhine.